As the world undergoes rapid political and economic transformations with escalating conflicts shaking the Middle East, the region has witnessed over a full year of genocide in Gaza – and no clear prospect for an end.

The conflict has expanded to southern Lebanon, reverberated in Yemen and Iraq, and reached Iran.

The Future of the Middle East series seeks to explore these challenges through interviewing prominent politicians, theorists, intellectuals, and current and former diplomats, providing various regional and international perspectives.

Through these discussions and insights, lessons from the past are shared in order to chart a path forward.

From the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict to regional interventions and the rise of new non-state actors, this series engages in enlightened discussions regarding what can be learned from history and how it will impact the region’s future.

It aims to explore visions for the future and highlight the vital role that Arab nations can play if historical alliances are revived, pushing towards sustainable stability while safeguarding their interests.

The structure of the series involves two parts – the first being a series of seven fixed questions based on requests from readers on the future of the region. The second part features questions tailored to the interviewees specific background, providing new insights into the overarching vision of the interview.

Ultimately, this series aims to explore how the Arab region can craft its own unified independent project – one free of external influence.

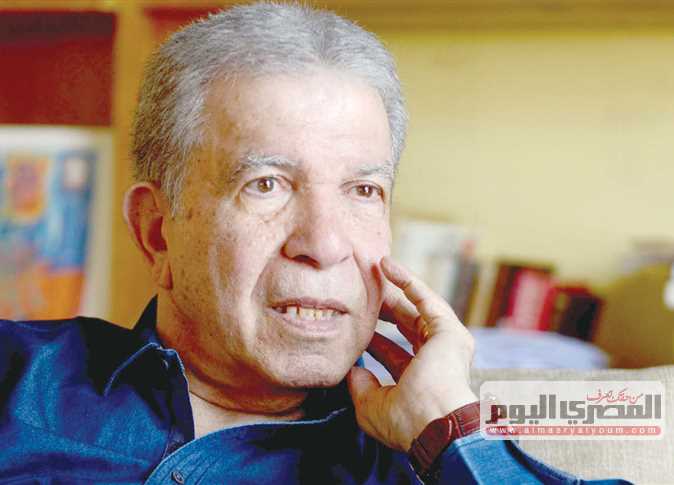

The Professor of International Relations and Political Economy at the American University in Cairo and Professor Emeritus at the University of Montreal, Canada, and Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, Bahgat Korany, stated that he believes the term “Middle East” has no scientific basis.

He considers it a relative, vague, and ambiguous term that allows international parties to include any country within it. He also asserts that the Israeli occupying state now acts as a superpower in the region, having become an established and undeniable presence.

It no longer needs the normalization it sought in past years, and can now act as it pleases, he warned.

Korany, the founder and former director of the American University Forum, stated that Israel’s brutal practices have made peace difficult at present. He emphasized the necessity of unifying Arab efforts to confront Israel’s brutality, deeming it the only way to achieve peace and stability in the region.

The professor also stressed the importance of strengthening the internal front of Arab countries, both materially (through education, health, and economy) and morally (through the relationship between the authorities and society).

He sees this as the optimal means to prevent the region from slipping into the abyss.

Interview:

■The term “Middle East” is a colonial geographical expression, yet it has become the prevalent term for the region encompassing Arab nations, Iran, Turkey, and other countries. Throughout history, the region has suffered from conflicts rooted in colonial schemes, turning it into a perpetually volatile spot on the world map. In your opinion, how do you see the reality of the region and the impact of history on this matter?

The “Middle East” as a term is an imported expression with absolutely no scientific basis. It is “middle” from whose perspective? Sometimes the French used the term “Near East” to refer to the area close to Europe (including Turkey, the Fertile Crescent, and the Levant), and “Far East” to refer to Asia.

Thus, the term merely reflects the perspective of those who coined it, without any scientific foundation.

Consequently, the division of the East into Near, Middle, and Far is relative and constrained by the viewpoint of whoever defined the framework.

Even in its applications, we find that the French campaign had an influence in establishing the term, as military leaders organized operations in terms of Near, Middle, and Far.

Despite this, ambiguity remains regarding the boundaries of the Middle East. Sometimes Pakistan was included within this so-called Middle East, and other times Cyprus and Greece, which makes the term both vague and ambiguous.

I’d like to share a personal experience here. After completing my doctorate in Switzerland, the University of Montreal asked me to teach international relations theory and assigned me the task of developing and heading a department focused on “Middle Eastern Studies.” This was in the 1970s. I rejected the proposed name and suggested the department be called “Studies of the Arab Region.”

This name initially met with opposition from the university administration, as it was considered unconventional and unfamiliar.

I argued that the Middle East is an area with unclear boundaries, and it would be more appropriate to base the department on a clearly defined entity, namely the Arab Region. I debated with the University of Montreal on the grounds that there is a regional institution for Arab states, the League of Arab States, whereas no international organization exists for the Middle East. This solidified the scientific basis for the concept of the “Arab Region” rather than the “Middle East,” which is based on a relative and fluid division and perspective subject to constant change.

They eventually accepted the naming, and subsequently established another program called “Jewish Studies.”

After that, I co-authored a book with Dr. Ali al Din Hilal on “The Foreign Policies of Arab States” to document the Arab reality, given the scarcity of writings on the foreign policies of Middle Eastern countries, specifically Arab ones. The goal of these research endeavors was to scientifically assert the Arab reality on the region, stemming from our understanding of who is within and who is outside the Arab region.

■The term “Middle East” emerged in American Alfred Mahan’s writings in 1902 before Condoleezza Rice spoke of the “New Middle East.” This concept is now strongly resurfacing amidst the Israeli war and the conflict with Iran. How do you view this plan, especially under the Trump administration and the rise of the right-wing in the US?

There is nothing new here.

The shift from the “old” to the “new” Middle East is fundamentally about integrating Israel into the region. In fact, Shimon Peres was the first to use the term “New Middle East,” discussing it after the late President Anwar Sadat’s visit to Israel and even publishing a book titled “The New Middle East.”

The term then gained widespread use. However, the crucial point here is that the word “new” draws attention to the idea of “change.” This prompted me and some colleagues to publish a book in 2008 titled “The Changing Middle East,” which was later translated into Arabic. It refutes the static view that believes the region is unchanging.

We finished writing the book in 2010, and right after publishing the Arab Spring wave emerged.

Some American media outlets considered the book to have predicted the Arab Spring, but in my interviews, for example, with CNN, I clarified that the book wasn’t a prediction but rather a diagnosis of the changes the region was undergoing.

Our role was akin to that of a geologist who observes changes and disturbances in the Earth’s layers without definitively predicting an earthquake.

I believe the region is currently undergoing new transformations, especially after the signing of the Abraham Accords.

■In your opinion, what should the major regional powers in the region, specifically Egypt and Saudi Arabia, as the two largest countries, do regarding these plans?

Arab coordination is fundamentally essential. In the era of the late leader Gamal Abdel Nasser and even now, some Nasserists still speak of Egypt as the great nation that should always lead the scene. However, the changes the region is experiencing make individual leadership illogical.

The region has changed, and thus individual leadership has become difficult.

Coordination with Saudi Arabia has become therefore become essential as Egypt and Saudi Arabia are the two main regional powers most knowledgeable about the area. However, this approach should be seen as a means for Arab mobilization, not for individual leadership.

Meaning, Saudi Arabia and Egypt are two fundamental pillars for Arab mobilization and forming a united Arab front, without monopolizing the spotlight and leading a region that is still undergoing change.

There’s a noticeable absence of a unified Arab project to counter the plans for the region, especially Israel’s expansionist goals clearly seen in Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria, and the talk of annexing more Arab territories. This direction was translated by Trump when he spoke of a “small Israel that must expand.”

How can Arabs formulate their project to confront these schemes? I believe in a scientific approach to analysis, and looking at the region, it’s clear that Israel is the military superpower. It can now do as it pleases, entering any territory and launching strikes without any losses to its air force carrying out these attacks.

The occupation forces entered Syria, reaching even the presidential palace and conducting strikes in its vicinity. They decided to seize Gaza and insist that most of the Strip will be part of Israel, despite initially claiming their war goal was to eliminate Hamas.

Now, however, they want Gaza’s land.

So, the diagnosis of the problem is that we are facing a state acting as a military superpower.

Based on this reality, we must seek the reasons that enabled Israel to reach this stage. When we were students after ’67, while studying in Switzerland in 1968, we met a French person of Jewish origin who gave us the best description of the Israeli situation: he said it represents settler colonialism.

I would now add the word “expansionist” to this description. The Israeli occupation’s primary concern is how to annex new territories, starting with the West Bank and Gaza, then requesting a portion of Sinai from Trump, and then turning its attention towards Saudi Arabia, trying to persuade Trump to pressure them to give Palestinians a part of their land, since they are interested in their cause.

Therefore, the expansionist aspect is fundamental to current Israeli thinking.

From this perspective, I believe the time is no longer appropriate for any peace with Israel under the current ruling elite in Tel Aviv. Peace will only happen with an internal change that brings calm and provides an opportunity for peace to prevail. The current government, its orientations, and its statements all indicate a desire to control the region.

In the past, what concerned Israel was normalization with the Arab region, but now normalization no longer matters to them because they already have everything they want.

The solution to this problem can only come through unifying Arab and non-Arab efforts to confront Israel’s brutal military force. Only then can we talk about peace. Discussing it with the current ruling class is a form of wasting time.

■Throughout history, Egypt has played key roles in the region. How can it continue to exercise these roles despite the surrounding challenges and the constant targeting it faces?

The reality is that the most prominent challenges we currently face are economic and our limited capabilities. However, from a purely scientific perspective, there are significant problems affecting the domestic situation, even if their cause is external, such as the water issue and the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), which Ethiopia has proceeded with building.

Hence, Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s view on this matter focused on the importance of the Arab region without neglecting relations with Africa, as Egypt’s life is linked to openness towards the African continent.

This leads us to the challenges of Egyptian foreign policy in Africa and the Arab world.

I believe that Egypt’s current approach of diversifying international relations is a very good direction, but it shouldn’t be limited to a specific capital or region. This also doesn’t mean excessive overstretch, where we become unable to control things, as challenges require setting priorities and dealing with them in a manner commensurate with capabilities.

Egypt is distinguished by its geographical location, which makes it a focus of interest for everyone who views it as “too expensive to fail,” meaning the failure of a country like Egypt cannot be accepted.

This is what drives the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to deal with Egypt.

The aid that comes to the country is not a “favor,” but rather its purpose is to protect the borders of donor countries against illegal immigration. However, this does not negate the necessity of achieving economic reform and self-sufficiency, away from reliance on aid, which creates dependency and undermines the ability of recipient countries to play an independent role.

Some ministers in past decades found it easy to incur debt, considering it a solution to the problem.

The unfortunate reality is that these debts affect the budget, especially the interest on these debts. A portion of the money we repay is debt service funds, like interest, not the principal debt itself. Historically, the basis of British colonialism was debt; before 1882, before the British entered Egypt, there was a meeting of the Egyptian government’s cabinet attended by experts from Egypt and England, with the aim of approving internal Egyptian policy because the country was indebted at the time.

I tell my students that the IMF dictates the economic policies of debtor countries.

It is the one that forces governments to adopt a market policy, where all goods and services are at market prices. The reality is that we are in a weak position, and the Fund is sometimes right about the importance of economic reform. But from our side, we must also focus on exports, not just real estate, despite its importance in attracting foreign currency.

I have colleagues at the Fund whom I urge to abandon traditional theory, given the new challenges that must be considered, as well as the situation of individuals in debtor countries.

Some populations cannot bear the high cost of education. If we don’t support education, there will be an ignorant populace. Therefore, we should choose the ordinary Islamic theory which states that one should choose the lesser harm, and it is not always necessary to follow the traditional theory that states raising the cost of everything to reduce consumption.

How can people abandon education? Thus, I offer recommendations to the Fund to adapt traditional theory according to the conditions of the people, and for their part, governments, to try to achieve some reforms.

■If you were to paint a picture of the future for this region, given the current conflicts and surrounding risks, how would you detail these scenarios?

I’d like to point out something that many Arab colleagues don’t often touch upon: external intervention is a significant problem, not to be underestimated. We suffered from colonialism for many years, and colonialism, or external control, still exists in some form.

Now, Israel has become a state imposed from outside, existing as one that aids external powers. Tel Aviv justifies its existence to the US by claiming it’s doing what Washington wants done on its behalf. One could say Israel is America’s aircraft carrier in the region.

So, there’s no doubt that external factors influence the region, but we also shouldn’t overlook internal factors. The region is fraught with problems, starting from population issues and water scarcity, leading up to political challenges. Some Arab regimes are still primarily concerned with tightening their grip on power while neglecting society.

Syria is the prime example of this.

In political science, there’s an important theory called “F-States,” short for “Fragile Failed States.”

Some Arab countries suffering from internal problems weaken the Arab world’s ability to assert itself. In the 1967 war, Israel controlled the battle within the first hour and a half or two hours, primarily through its air force, by bombing Egyptian aircraft on the ground. Once air superiority was achieved, the battle was over.

The truth is, the 1967 defeat wasn’t just the problem; it was the level of the defeat, one of the reasons for which was the level of education.

Some conscripts didn’t even know how to operate tanks, so they would jump out of them. That’s why after 1967, conscription focused on university graduates. Initially, they would serve for one year, but then they continued their service for six to seven years.

Hence, when Moshe Dayan was asked after the 1973 war about the reasons for their losses compared to their gains in ’67 and what had changed in Israel’s forces, Dayan said that his forces hadn’t changed, but what had changed were the Arabs.

Therefore, the internal front is crucial: education, health, and the economic situation. Without supporting these factors, a state falls into the trap of becoming a “fragile state.”

Many, in reality, speak only of external factors, neglecting the internal factors which are of great importance.

A state’s openness to its society also gives it the strength to resist external factors. Authoritarian states might succeed for a period, but they eventually fade away. Syria, as an Arab power, is now paralyzed and will remain so for some time.

Bashar resisted change and imposed himself, which negatively impacted society and led to its deterioration. Israel capitalized on this, dismantling the Syrian army’s infrastructure and seizing the Golan Heights.

Now, it’s conducting strikes near the presidential palace – I believe there’s no stronger message than that.

I re-emphasize that strengthening the internal front materially (in terms of education, health, and economy) and morally (in terms of the relationship between the authorities and society) is of utmost importance.

Exclusive interview with AUC professor Bahgat Korany discusses Middle East crisis, ‘futility’ of peace talks with Israel Egypt Independent.

Read More Details

Finally We wish PressBee provided you with enough information of ( Exclusive interview with AUC professor Bahgat Korany discusses Middle East crisis, ‘futility’ of peace talks with Israel )

Also on site :

- 7 pet-friendly Colorado hotels for your next getaway or roadtrip

- The Mid-Morning Habit Cardiologists Are Begging You to Never, Ever Do

- Chipotle’s new CEO is bringing back a missing ingredient to hit the chain’s next goal—raising annual sales per store to $4 million